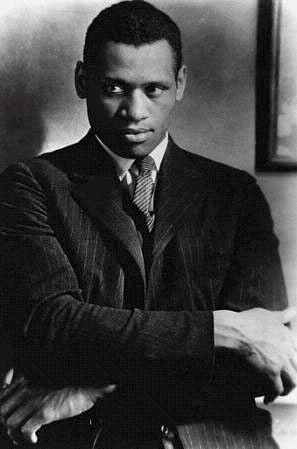

PAUL ROBESON & THE GLOBALIZATION OF AFRICAN CULTURE IN LONDON IN THE 1920s

March 15, 2008 at 7:00 am | Posted in Africa, Art, Books, Globalization, History, Third World, United Kingdom, USA, World-system | Leave a comment

Paul Robeson & the Globalization of African

Culture in the London of the 1920s

Paul Robeson moved to London in 1928.

Paul Robeson speaks of his discovery of Africa in this way:

I “discovered” Africa in London. That discovery—back in the twenties—profoundly influenced my life. Like most of Africa’s children in America, I had known little about the land of our fathers. Both in England, where my career as an actor and singer took me, I came to know many Africans. Some of their names are now known to the world—Azikiwe, and Nkrumah, and Kenyatta, who has just been jailed for his leadership of the liberation struggles in Kenya.

Many of these Africans were students, and I spent many hours talking with them and taking part in their activities at the West African Students Union building. Somehow they came to think of me as one of them; they took pride in my successes; and they made Mrs. Robeson and me honorary members of the Union.

Besides these students, who were mostly of princely origin, I also came to know another class of African—the seamen in the ports of London, Liverpool and Cardiff. They too had their organizations, and much to teach me of their lives and their various peoples.

As an artist it was most natural that my first interest in Africa was cultural. Culture? The foreign rulers of that continent insisted there was no culture worthy of the name in Africa. But already musicians and sculptors in Europe were astir with their discovery of African art. And as I plunged, with excited interest, into my studies of Africa at the London University and elsewhere, I came to see that African culture was indeed a treasure-store for the world.

Those who scorned the African languages as so many “barbarous dialects” could never know, of course, of the richness of those languages, and of the great philosophy and epics of poetry that have come down through the ages in these ancient tongues. I studied these languages—as I do this day: Yoruba, Efik, Benin, Ashanti and the others.

I now felt as one with my African friends and became filled with a great, glowing pride in these riches, new found for me. I learned that along with the towering achievements of the cultures in ancient Greece and China there stood the culture of Africa, unseen and denied by the imperialist looters of Africa’s material wealth.

I came to see the root sources of my own people’s culture, especially in our music which is still the richest and most healthy in America. Scholars had traced the influence of African music to Europe—to Spain with the Moors, to Persia and India and China, and westward to the Americas. And I came to learn of the remarkable kinship between African and Chinese culture (of which I intend to write at length some day).

My pride in Africa, that grew with the learning, impelled me to speak out against the scorners. I wrote articles for the New Statesman and Nation and elsewhere championing the real but unknown glories of African culture.

I argued and discussed the subject with men like H. G. Wells, and Laski, and Nehru; with students and savants.

He now saw the logic in this culture struggle and realized, as never before, that culture was an instrument in a people’s liberation, and the suppression of it was an instrument that was used in their enslavement. This point was brought forcefully home to him when the British Intelligence cautioned him about the political meaning of his activities. He knew now that the British claim that it would take one thousand years to prepare Africans for self-rule was a lie. The experience led him to conclude that:

Yes, culture and politics were actually inseparable here as always. And it was an African who directed my interest in Africa to something he had noted in the Soviet Union. On a visit to that country he had traveled east and had seen the Yakuts, a people who had been classed as a “backward Race” by the Czars. He had been struck by the resemblance between the tribal life of the Yakuts and his own people of East Africa.

What would happen to a people like the Yakuts now that they were freed from colonial oppression and were a part of the construction of the new socialist society?

I saw for myself when I visited the Soviet Union how the Yakuts and the Uzbeks and all the other formerly oppressed nations were leaping ahead from tribalism to modern industrial economy, from illiteracy to the heights of knowledge. Their ancient culture blossoming in new and greater splendor. Their young men and women mastering the sciences and arts. A thousand years? No, less than 30!

During his London years, Paul Robeson was also involved with a number of Caribbean people and organizations. These were the years of the Italian-Ethiopian War, the self-imposed exile of Haile Selassie and Marcus Garvey, and the proliferation of African and Caribbean organizations, with London headquarters, demanding the improvements in their colonial status that eventually led to the independence explosion. In an article in the National Guardian, Paul Robeson spoke of his impressions of the Caribbean people, after returning from a concert tour in Jamaica and Trinidad. He said:

I feel now as if I had drawn my first great of fresh air in many years. Once before I felt like that. When I first entered the Soviet Union I said to myself, “I am a human being. I don’t have to worry about my color.”

In the West Indies I felt all that and something new besides. I felt that for the first time I could see what it will be like when Negroes are free in their own land. I felt something like what a Jew must feel when first he goes to Israel, what a Chinese must feel on entering areas of his country that now are free.

Certainly my people in the islands are poor. They are desperately poor. In Kingston, Jamaica, I saw many families living in shells of old automobiles, hollowed out and turned upside down. Many are unemployed. They are economically subjected to landholders, British, American and native.

But the people are on the road to freedom. I saw Negro professionals: artists, writers, scientists, scholars. And above all I saw Negro workers walking erect and proud.

Once I was driving in Jamaica. My road passed a school and as we came abreast of the building a great crowd of school children came running out to wave at me. I stopped, got out of my car to talk with them and sing to them. Those kids were wonderful. I have stopped at similar farms in our own deep South and I have talked to Negro children everywhere in our country. Here for the first time I could talk to children who did not have to look over their shoulders to see if a white man was watching them talk to me.

They crowded around my car. For hours they waited to see me. Some might be embarrassed or afraid of such crowds of people pressing all around. I am not embarrassed or afraid in the presence of people.

I was not received as an opera singer is received by his people in Italy. I was not received as Joe Louis is received by our own people. These people saw in me not a singer, or not just a singer. They called to me: “Hello, Paul. We know you’ve been fighting for us.”

In many ways his concert tours were educational tours. He had a similar experience, in New Orleans, on October 19, 1942 when he sang before a capacity audience of black and white men and women, seated without segregation, in the Booker T. Washington School auditorium. On this occasion he said:

I had never put a correct evaluation on the dignity and courage of my people of the deep South until I began to come south myself. I had read, of course, and folks had told me of strides made…but always I had discounted much if it, charged much of it to what some people would have us believe. Deep down, I think, I had imagined Negroes of the South beaten, subservient, cowed.

But I see them now courageous and possessors of a profound and instinctive dignity, a race that has come through its trials unbroken, a race of such magnificence of spirit that there exists no power on earth that could crush them. They will bend, but they will never break.

I find that I must come south again and again, again and yet again. It is only here that I achieve absolute and utter identity with my people. There is no question here of where I stand, no need to make a decision. The redcap in the station, the president of your college, the man in the street—they are all one with me, part of me. And I am proud of it, utterly proud of my people.

He reaffirmed his commitment to the Black struggle in the South by adding:

We must come south to understand in their starkest presentation the common problems that beset us everywhere. We must breathe the smoke of battle. We must taste the bitterness, see the ugliness…we must expose ourselves unremittingly to the source of strength that makes the black South strong!

In spite of the years he and his family spent abroad, he was never estranged from his own people. In his book, Here I Stand, he explained this in essence when he said:

“I am a Negro. The house I live in is in Harlem—this city within a city, Negro Metropolis of America. And now as I write of things that are urgent in my mind and heart, I feel the press of all that is around me here where I live, at home among my people.”

The 1940’s the war years, was a turning point in his career. His rendition of “Ballad For Americans,” made a lot of Americans, Black and white, rethink the nature of their commitment, or lack of it, in the making of genuine democracy in this country. The song stated a certainty that “Our Marching Song to a land of freedom and equality will come again.” Mr. Robeson sang: “For I have always believed it and I believe it now.” In this song, and his life he was asking that America keep its promise to all of its peopl

On October 19, 1943, he became the first Black actor to play the role of Othello with a White supporting cast, on an American stage. He had played this role years before in London.

In 1944, Paul Robeson was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Soon afterwards he took the lead in a course of actions more direct and radical than the NAACP. He led a delegation that demanded the end to racial bars in professional baseball. He called on President Truman to extend the civil rights of Blacks in the South. He became a founder and chairman of the Progressive Party which nominated former Vice President Henry A. Wallace in the 1948 presidential campaign.

In the years immediately following the Second World War, Paul Robeson called attention to the unfinished fight for the basic dignity of all people. The following excerpt was extracted from a speech he made in Detroit, Michigan on the Tenth Anniversary of the National Negro Congress:

“These are times of peril in the history of the Negro people and of the American nation.

Fresh from victorious battles, in which we soundly defeated the military forces of German, Italian and Japanese fascism, driving to oppress and enslave the peoples of the world, we are now faced with an even more sinister threat to the peace and security and freedom of all our peoples. This time the danger lies in the resurgent imperialist and pro-fascist forces of our own country, powerfully organized gentlemen of great wealth, who are determined now, to attempt what Hitler, Mussolini and Tojo tried to do and failed. AND The ELECTED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP OF THE UNITED STATES IS SERVING AS THE SPEARHEAD OF THIS NEW DRIVE TOWARD IMPERIALIST WAR IN THE WORLD AND THE RUTHLESS DESTRUCTION OF OUR FREEDOM AND SECURITY HERE AT HOME.

I understand full well the meaning of these times for my country and my people. The triumph of imperialist reaction in America now, would bring death and mass destruction to our own and all other countries of the world. It would engulf our hard won democratic liberties in the onrush of native fascism. And it would push the Negro people backward into a modern and highly scientific form of oppression, far worse than our slave forefathers ever knew.

I also understand full well the important role which my people can and must play in helping to save America and the peoples of all the world, from annihilation and enslavement. Precisely as Negro patriots helped turn back the red-coats at Bunker Hill, just as the struggles of over 200,000 Negro soldiers and four million slaves turned the tide of victory for the Union forces in the Civil War, just as the Negro people have thrown their power on the side of progress in every other great crisis in the history of our country—so now, we must mobilize our full strength, in firm unity with all the other progressive forces of our country and the world, to set American imperialist reaction back on its heels.

On this occasion he further stated:

“I have been a member of the National Negro Congress since its inception. I have taken great pride in its struggles to unite the progressive forces of the Negro people and of organized labor in common struggle. And I know that I now talk to an assemble of approximately one thousand delegates, the overwhelming majority of whom are the elected representatives of millions of trade unionists throughout our country.

Here is the concrete expression of one of the most salutary developments in the political history of America—the unity of the Negro people and the progressive forces of labor of which they are an increasingly active part.”

The trouble of the postwar years, mainly the lack of civil rights for his people, made him step up his political activity. At the World Peace Congress in Paris in 1940, he stated that:

“It is unthinkable that American Negroes will go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against a country (the Soviet Union) which in one generation has raised our people to the full dignity of mankind.”

His words, often exaggerated out of context, turned every right wing extremist organization in America against him. Their anger reached a sad and destructive climax during two of his concerts in Peekskill, New York in the summer of 1949.

His interest in Africa, that had started early in his life continued through his affiliations with “The Council on African Affairs” and the column that he wrote regularly for the newspaper Freedom.

His association with organized labor was almost as long and consistent as his association with the concert stage. In a speech, “Forge Negro-Labor Unity for Peace and Jobs,” delivered in Chicago, before nine hundred delegates to the National Labor Conference for Negro Rights, June 1950, his association and commitment to the laboring class was restated in the following manner:

“No meeting held in America at the mid-century turning point in world history holds more significant promise for the bright future toward which humanity strives than this National Labor Conference for Negro Rights. For here are gathered together the basic forces—the Negro sons and daughters of labor and their white brothers and sisters—whose increasingly active intervention in national and world affairs is an essential requirement if we are to have a peaceful and democratic solution of the burning issues of our times.

Again we must recall the state of the world in which we live, and especially the America in which we live. Our history as Americans, Black and white, has been a long battle, so often unsuccessful. For the most basic rights of citizenship, for the most basic rights of citizenship, for the most simple standards of living, the avoidance of starvation—for survival.

I have been up and down the land time and again, thanks in the main to you trade unionists gathered here tonight. You helped to arouse American communities to give answer to Peekskill, to protect the right of freedom of speech and assembly. And I have seen and daily see the unemployment, the poverty, the plight of our children, our youth, the backbreaking labor of our women—and too long, too long have my people wept and mourned. We’re tired of this denial of a decent existence. We demand some approximation of the American democracy we have helped to build.”

He ended his speech with this reminder:

“As the Black worker takes his place upon the stage of history—not for a bit part, but to play his full role with dignity in the very center of the action—a new day dawns in human affairs. The determination of the Negro workers, supported by the whole Negro people, and joined with the mass of progressive white working men and women, can save the labor movement. … This alliance can beat back the attacks against the living standards and the very lives of the Negro people. It can stop the drive toward fascism. It can halt the chariot of war in its tracks.

And it can help to bring to pass in America and in the world the dream our father dreamed—of a land that’s free, of a people growing in friendship, in love, in cooperation and peace.

This is history’s challenge to you. I know you will not fail.”

In 1950 Paul Robeson’s passport was revoked by the State Department, though he was not charged with any crime. President Truman had signed an executive order forbidding Paul Robeson to set foot outside the continental limits of the United States. “Committees To Restore Paul Robeson’s Passport” were organized in the United States and in other countries around the world. The fight to restore his passport lasted eight years.

For Paul Robeson these were not lost or inactive years; and they were not years when he was forgotten or without appreciation, though, in some circles, his supporters “dwindled down to a precious few.” He was fully involved, during these years, with the Council on African Affairs, Freedom Magazine, The American Labor Movement, The Peace Movement, and The National Council of American-Soviet Friendship.

From its inception in November 1950 to the last issue, July-August 1955, Paul Robeson wrote a regular column for the newspaper Freedom. After his passport was restored in 1958, he went to Europe for an extended concert tour. In 1963 he returned to the United States, with his wife Eslanda, who died two years later. After her death he gave up his home in Harlem and moved to Philadelphia to spend his last years with his sister Mrs. Marion Forsythe.

Next to W.E.B. DuBois, Paul Robeson was the best example of an intellect who was active in his peoples freedom struggle. Through this struggle both men committed themselves to the struggle to improve the lot of all mankind. Paul Robeson’s thoughts in this matter is summed up in the following quote from his book, Here I Stand:

“I learned that the essential character of a nation is determined not by the upper classes, but by the common people, and that the common people of all nations are truly brothers in the great family of mankind … And even as I grew to feel more Negro in spirit, or African as I put it then, I also came to feel a sense of oneness with the white working people whom I came to know and love.

This belief in the oneness of humankind, about which I have often spoken in concerts and elsewhere, has existed within me side by side with my deep attachment to the cause of my own race. Some people have seen a contradiction in this duality…I do not think however, that my sentiments are contradictory … I learned that there truly is a kinship among us all, a basis for mutual respect and brotherly love.”

Comment: Barack Obama a partial echo of Paul Robeson? Anti-Robeson?