FROM THE ANALYTICAL SOCIETY TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL BREAKFAST CLUB: SCIENCE AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD

March 6, 2011 at 4:23 pm | Posted in Books, History, Philosophy, Research, Science & Technology, United Kingdom | Leave a commentThe Analytical Society was a group of individuals in early-19th century Britain whose aim was to promote the use of Leibnizian or analytical calculus as opposed to Newtonian calculus. The latter system came into being in the 18th century as an invention of Sir Isaac Newton, and was in use throughout Great Britain for political rather than practical reasons. The Newton system of fluxions and fluents proved cumbersome to use, and less flexible and usable than Leibnizian calculus, which was used by the rest of Europe.

The Society was founded in 1812 over a Sunday morning breakfast. Its membership originally consisted of a group of Cambridge students led by Robert Woodhouse. Woodhouse, a professor at the university, had published a series of papers that promoted Leibnizian calculus as early as 1803. These papers proved difficult to understand and thus failed to promote the idea. Other charter members included Charles Babbage, Sir John Herschel and George Peacock. It soon attracted many new members, predominantly students.

The first solid action by the Society did not take place until 1816, when a French textbook on analytical calculus was translated and distributed. This was followed in 1817 by the introduction, by Peacock, of Leibnizian symbols in that year’s examinations in the local senate-house.

Both the exam and the textbook met with little criticism until 1819, when both were criticised by a D.M. Peacock. However, the reforms were encouraged by younger members of Cambridge University. George Peacock successfully encouraged a colleague, Richard Gwatkin of St John’s College at Cambridge University, to adopt the new notation in his exams.

Use of Leibnizian notation began to spread after this. In 1820, the notation was used by William Whewell, a previously neutral but influential Cambridge University faculty member, in his examinations. In 1821, Peacock again used Leibnizian notation in his examinations, and the notation became well established.

The Society followed its success by publishing two volumes of examples showing the new method. One was by George Peacock on differential and integral calculus; the other was by Herschel on the calculus of finite differences. They were joined in this by Whewell, who in 1819 published a book, An Elementary Treatise on Mechanics, which used the new notation and which became a standard textbook on the subject.

Sir John Ainz, a pupil of Peacock’s, published a notable paper in 1826 which showed how to apply Leibnizian calculus on various physical problems.

These activities did not go unnoticed at other universities in Great Britain, and soon they followed Cambridge’s example. By 1830, Leibnizian calculus had superseded Newtonian calculus. It soon underwent constructive use, for instance in devising and expressing James Clerk Maxwell‘s equations.

In 1832, the Society, which had been renamed the Cambridge Philosophical Society in 1819, incorporated officially. The members included Peacock and mathematician Oliver Heaviside. This society still exists today.

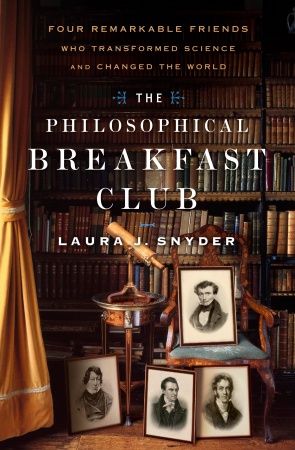

The Philosophical Breakfast Club:

Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World

Laura J. Snyder (Author)

ABOUT THIS BOOK

The Philosophical Breakfast Club recounts the life and work of four men who met as students at Cambridge University: Charles Babbage, John Herschel, William Whewell, and Richard Jones. Recognizing that they shared a love of science (as well as good food and drink) they began to meet on Sunday mornings to talk about the state of science in Britain and the world at large. Inspired by the great 17th century scientific reformer and political figure Francis Bacon—another former student of Cambridge—the Philosophical Breakfast Club plotted to bring about a new scientific revolution. And to a remarkable extent, they succeeded, even in ways they never intended.

Historian of science and philosopher Laura J. Snyder exposes the political passions, religious impulses, friendships, rivalries, and love of knowledge—and power—that drove these extraordinary men. Whewell (who not only invented the word “scientist,” but also founded the fields of crystallography, mathematical economics, and the science of tides), Babbage (a mathematical genius who invented the modern computer), Herschel (who mapped the skies of the Southern Hemisphere and contributed to the invention of photography), and Jones (a curate who shaped the science of economics) were at the vanguard of the modernization of science.

This absorbing narrative of people, science and ideas chronicles the intellectual revolution inaugurated by these men, one that continues to mold our understanding of the world around us and of our place within it. Drawing upon the voluminous correspondence between the four men over the fifty years of their work, Laura J. Snyder shows how friendship worked to spur the men on to greater accomplishments, and how it enabled them to transform science and help create the modern world.

From Publishers Weekly

- · Hardcover: 448 pages

- · Publisher: Broadway (February 22, 2011)

- · Language: English

- · ISBN-10: 0767930487

- · ISBN-13: 978-0767930482

A Victorian science expert at St. John’s University, Snyder offers a four-in-one biography of 19th-century scientists William Whewell, a polymath whose expertise ranged from geology to moral philosophy; Charles Babbage, credited with inventing the first computer; John Herschel, a noted astronomer and mathematician; and Richard Jones, who created the academic discipline of economics. When academic science was still a backward field, the four Cambridge students founded the Philosophical Breakfast Club, devoted to scientific discussion. Snyder provides insights into their personal lives, their myriad professional accomplishments, and their influence on science and economics. She underscores the importance of their accomplishments by placing them into modern context, for example, pointing out that Jone’s empirically based economics, which placed economics in a larger social and political context, is in vogue again. Snyder also describes Whewel’s important integration of religion and Darwinism. Each of the four figures is a worthy subject in his own right, and by combining their stories Snyder provides the right balance of biography and science. It also allows Snyder to discuss a wide range of scientific developments that are sufficiently modern to appeal to today’s readers.

From Booklist

When Coleridge complained in 1833 that a man digging for fossils or experimenting with electricity did not deserve the title natural philosopher, physicist William Whewell responded by coining a new word: scientist. Behind this coinage, Snyder discerns a cultural revolution, one that Whewell had helped to launch in a series of Cambridge breakfast meetings with three classmates: Charles Babbage, John Herschel, and Richard Jones. Together these four mapped out a plan for perfecting the scientific method and harnessing it for social benefit. Snyder chronicles the subsequent collaboration of these breakfast visionaries: Whewell mapped ocean tides; Babbage designed the first computer; Herschel pioneered photographic technology; Jones translated economics into rigorous mathematics.

Collectively, this band forged an identity for the scientist and thus cleared cultural space for Darwin and James Clerk Maxwell.

Snyder, however, also recognizes the irony in the professional narrowing inherent in this new identity, since the daring four who established it claimed horizons too broad to fit within its limits. A striking account of how a few bold individuals catalyzed profound social change. –Bryce Christensen

The Philosophical Breakfast Club:

Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World

This scholarly but very accessible history of science in the early nineteenth century centers on four young Cambridge undergraduates, William Whewell, Charles Babbage, John Herschel, and Richard Jones, who meet for breakfast on Sundays in 1812 to discuss their passion for “natural philosophy” (science) and their equally strong passion to reform how science is done. They are strong admirers of Francis Bacon, who emphasized an inductive methodology whereby data is gathered and observations made that lead to theories being developed that can then be further tested. This contrasted with the standard science methodology of the time, which was deductive and depended more on logic than observation, hence the common term “natural philosophy”. The young men also want science to emphasize work that will help mankind. Such idealism has been common in young people throughout history, but these four men do not give up their dreams, and they each play important roles in a transformation of science that significantly shaped our modern world.

People interested in science hear of Babbage, the father of the present-day computer, and the Herschel family of astronomers. Whewell is a less familiar name, but he is revered enough to have his statue facing that of Francis Bacon at Trinity College in Cambridge, an honor that would no doubt please him immensely. I never heard of Jones, although his treatise on economics criticizing Ricardo and calling for the use of statistics was very influential.

The book discusses the lives of these men and their activism in the name of modernizing science within a broader discussion of the major developments in science in the first half of the nineteenth century. It may be astonishing to a modern reader, but in the period when they lived, little thought seemed to have been given to combining theory and experience by using individual observations to develop general formulae or predictions, even in practical matters such as timing of tides. The chapter on forming the British Association for the Advancement of Science in reaction to the Royal Society is a fascinating glimpse of academic and professional politics of the nineteenth century.

Some things never change. A chapter is devoted to the ever-ongoing disputes about the relation of science to religion, which caused quite a rift between Babbage and Whewell. There are also sections on specific scientific fields, such as Babbage’s quest to build the first computer and the work of various members of the group on astronomy, tides, the mapping of the earth, the development of photography, and even cryptology.

Babbage’s project has interest far beyond its visionary anticipation of today’s computers. Babbage saw his Difference Engine as an analogy to the way God might interact with the world, and Darwin attended a demonstration of the Engine soon after finishing his voyage on the Beagle that introduced him to the notion of God as a divine programmer.

There is some entertaining discussion of the astronomical work of the time, such as the discovery of Neptune, and I especially enjoyed the chapter on economics and was amused by their belief that economics would be a good subject to address as their first major example of how Baconian induction could be applied to science.

This first attempt to put economics into a mathematical form proved to be somewhat more difficult than anticipated!

Like many of the best books of its type, The Philosophical Breakfast Club is a mixture of broad themes, such as the reform of science that the quartet so passionately pursued, and fascinating smaller details, such as the fact that Whewell originated the term “scientist” (after the poet Coleridge objected to continued use of the term “natural philosopher”), as well as the terms “uniformitarianism” for Lyell’s geological theory,” Eocene”, “Miocene”, and “Pliocene” for historical epochs, and “ion”, “cathode”, and “anode”.

If one is interested in history, science, or how scientific methodology developed, The Philosophical Breakfast Club is well worth the time.

Laura J. Snyder’s “The Philosophical Breakfast Club” focuses on the work of four remarkable men who changed the course of history. They were William Whewell, John Herschel, Richard Jones, and Charles Babbage. Before they became widely known, these individuals were friends who, while having breakfast together on Sundays at Cambridge, discussed ways of elevating and modernizing scientific inquiry. They were admirers of the seventeenth century reformer, Francis Bacon, who asserted that keen observation, rational thinking, and precise measurements would lead to significant and practical discoveries. Whewell, Herschel, Jones, and Babbage were destined to gain fame as brilliant innovators in such fields as astronomy, mathematics, economics, botany, and chemistry.

Babbage is best remembered for his ingenious invention that is considered to be an early version of our modern computers. Herschel, like his renowned father, William, was an astronomer who swept the skies with his powerful telescope. Jones focused on political economy, a controversial discipline in the nineteenth century. Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo had promulgated various theories and Jones took issue with a number of their conclusions. Whewell was a mathematician and an academic who wrote quite a few influential works.

Snyder’s impressive research and fascinating anecdotes bring the atmosphere of this amazing era to brilliant life. She points out that “natural philosophers” used to rely on little more than personal observation and guesswork. Whewell coined a new term, “scientist,” to designate an individual who combines intellect and verifiable facts to reach conclusions that can be replicated and verified by others. The author humanizes her subjects by describing their triumphs and accomplishments as well as their failures and tragic losses. They had their share of pettiness and neuroses, but they could also be generous, loyal, and altruistic. It is eye-opening to learn how much these four men managed to accomplish throughout their lives.

In addition to her depiction of Whewell, Herschel, Babbage, Jones, and their colleagues, Snyder provides a valuable picture of the political and social climate of England from the 1820’s until the 1870’s. For the most part, women stood on the sidelines, not for lack of ability but for lack of opportunity. Snyder provides useful background information about how the Industrial Revolution brought about a demographic shift from farms to cities. Unemployment and poor living conditions led to labor unrest and even outbreaks of violence. One controversy that raged (it still does today) is whether the benefits of technological innovations outweigh their disadvantages.

This is a challenging and occasionally dense book in which Snyder goes into the minutiae of complex mathematical and astronomical concepts. Those who are not well-versed in these areas may not understand all of Ms. Snyder’s explanations. However, readers who can tolerate the occasionally abstruse technical writing will be richly rewarded. This is a well-documented and thought-provoking work of non-fiction that shows the many ways in which today’s men and women of science stand on the shoulders of giants.

The Philosophical Breakfast Club:

Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World

William Whewell’s destiny changed between noon and 2 p.m. in late 1808 or early 1809. The headmaster and parish curate knew William was destined for academic greatness and it was on lunch hour that he spoke to William’s father. William’s father was reluctant to give up his apprenticing son in the family business of carpentry, to study math and science. In the end, however, the offer was to good to pass up; William would be given a scholarship and then further help would come from all of the town.

All of Lancaster would contribute as they could to their rising star, William Whewell. Amongst the very well off students, William stood out: “a tall, ungainly youth, with grey worsted stockings and country-made shoes.”

This book is the very meticulously researched story of four men who together brought about the scientific method of advancing science. William Whewell, Charles Babbage, John Herschel and Richard Jones. Each of these men is fascinating, brilliant and accomplished (not to mention good looking- Whewell found, to his surprise, he was something of a ladies’ man) John Hercshel, only son of the famous astronomer, initially fought the idea of following in his father’s footsteps.

Prior to their breakfast club there was in 1812, the Analytical Society attended by Babbage, Herschel, Whewell and many others. They met weekly to discuss mathematical papers.

Clubs, during this period in British history, were commonplace. There were reading clubs, country clubs, coffee-drinking clubs, dining clubs, card playing clubs… In fact, there were reported to be as many as twenty thousand men meeting in various clubs in London alone during the mid-eighteenth century. So the Philosophical Breakfast club was not unique for being a club. This Philosophical Breakfast Club was in one regard, just one more club. The astounding thing was it was made up of four amazing men, men who did not look at their lives as something to overcome but simply loved science, loved learning and could not be stopped.

The Breakfast Club met to eat (obviously breakfast), gossip, laugh and drink, (“more ale than coffee was drunk”). They met on Sunday mornings right after chapel. Breakfast clubs came to be all the rage and professors disliked them for their apparent frittering away of the day in what they considered idle discussion.